An approximately 22-yard stretch inside the Institute of Jamaica compresses Jamaican music history into a quick tour of several centuries. Set up on International Reggae Day (July 1) 2009, the mini-exhibition is the seed of the Jamaica Music Museum, headed by Herbie Miller.

Beginning with Jamaica’s earliest known inhabitants – the Tainos, under the heading ‘One People, One Voice, One Song’, it states “from earliest times until today, music has been a source of inspiration that has allowed Jamaicans to endure, resist and dream. Music represents events from procreation to burial”. Unexpectedly, the sound of identity developed into a source of income. The museum goes into the earliest recorded phase of Jamaican popular music with mento at Stanley Motta’s studio on Hanover Street, followed by the sound of Independence in 1962, ska. After that came the short-lived but still influential rocksteady (about 1967 – 1968), then reggae and finally dancehall, starting in the early 1980s.

Despite Byron Lee and the Dragonaires’ introduction of ska to the New York World’s Fair in 1964, the year of Millie Small’s one-off international ska success ‘My Boy Lollipop’ (which went on to sell seven million copies), it is reggae and dancehall which have become indelible parts of worldwide music.

REGGAE’S ROOTS

Who made the first reggae song is debatable – The Cables ‘Baby Why’ and The Heptones’ ‘I Shall Be Released’ among the double handful of candidates. There is no doubting, though, who first used the term reggae, which was to become a catch-all for Jamaican popular music, on record. Though the spelling was different, it was Toots and the Maytals who recorded ‘Do the Reggay’ in 1968 for producer Leslie Kong.

By the early 1970s reggae had literally caught a fire outside Jamaica, through first The Wailers (Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer) and then the renamed Bob Marley and Wailers. The Wailers did not start reggae, but from the 1973 ‘Catch a Fire’ through to the 1980 ‘Uprising’, the last studio album released when Bob Marley was alive, with Marley’s frenetic stage movement and incredibly expressive vocals they defined its international imprint.

The word ‘international’ is key. The definitive Island Records Marley albums sounded different from the standard Jamaican fare of the time. This was done through the overdubs in England for ‘Catch a Fire’, where rock guitar leads were added by Wayne Perkins and keyboards by John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrich. As Bundrich said in the documentary on the making of the album, “we needed to add a little bit of something that Americans were used to”. There was also the way the music was mixed, the bass de-emphasized by engineer Tony Platt from the rumbling sound shaped for the sound systems that have molded Jamaican popular music since the 1950s. As Island boss Chris Blackwell said in the documentary, “this record was the most… I don’t say softened, but I’d more say enhanced to try and reach a rock market”.

During the 1970s, though, there was another stream of reggae running in Jamaica, true to the drum and bass roots. Dennis Brown (reportedly more popular in Jamaica than Bob Marley during the 1970s), Burning Spear (his 1977 album ‘Marcus Garvey’ a classic by any measure), Culture (‘Two Sevens Clash’, 1977), Peter Tosh (‘Legalise It’, 1976) and Bunny Wailer (‘Blackheart Man’, 1977) were among those releasing albums which were rocking Jamaica with undiluted drum and bass. Another seminal early ’70s product, the 1972 film ‘The Harder They Come’, presented the more Jamaican sound, including the title track by Jimmy Cliff and The Melodians’ ‘Rivers of Babylon’.

THE BIRTH OF DANCEHALL

Marley’s death on May 11, 1981, may or may not have facilitated the rise of dancehall, which Dr Donna Hope says in her 2006 book Inna De Dancehall “can be defined as that genre of Jamaican popular music that originated in the early 1980s”. She notes “… dancehall music is critically exiled from all preceding genres of Jamaican music culture”. Certainly, within two years of the Marley’s death, deejay Yellowman’s performance at Reggae Sunsplash 1982 had done a lot to firmly establish the dancehall sound on the pivotal festival; not that dancehall, with deejays at the core, had not been around before the albino inverted his apparent physical disadvantage to proclaim unabashed sexuality, with resounding success. In the 1980s, though, they really hit stride, and dancehall, as defined by Hope and others, became the major sound in Jamaica, beginning the longest dominant period of any indigenous popular Jamaican music form.

The seismic shifting point came in February 1985 with the release of the Sleng Teng rhythm, a slowed down version of a preset rhythm on a Casio MT 40 keyboard adjusted by Noel Davy. Ironically, Jamaica’s first digitally created rhythm hit the airwaves almost simultaneously with inclusion of reggae in the American Grammy Awards, roots reggae group Black Uhuru winning the first golden gramophone with ‘Anthem’.

Ironic too, that while reggae was on the wane in Jamaica it was taking firmer hold abroad. The first importees were from England, where Jamaicans had gone as part of the Windrush generation in the early 1950s – Steel Pulse, Aswad and UB40 leading the drum and bass charge. Since then there have been reggae singers from every continent, notably Africa (Alpha Blondie, Lucky Dube), with Hawaii and Japan having their own sub-genres of reggae. And there was a descendant of Jamaican music in hip-hop, which had its roots in Jamaican Clive ‘Kool Herc’ Campbell operating a sound system in New York in the mid-1970s, doing mixing styles and toasting which was picked up by hip-hop pioneers Grandmaster Flash and Africa Bambaataa. Fully in its element, the digital music-making approach allowing more persons to make music with fewer musicians (or even one) and the pattern of several persons recording on one ‘riddim’ established, the stage was set for the emergence of modern dancehall.

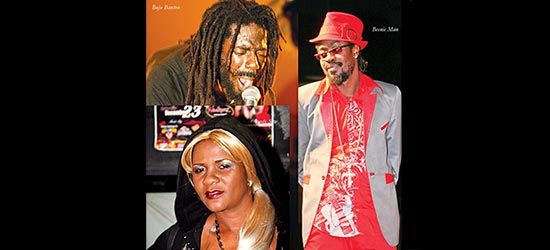

Reggae has not disappeared, although it went into recession in the 1990s, Beres Hammond among the few reggae singers with continuing appeal to the dancehall audience. With Capleton leading a resurgence of Rastafari in dancehall in the mid-1990s, followed by Buju Banton, there have been those deejays – especially Sizzla who have transitioned easily between the two. In addition, family group Morgan Heritage kept the reggae banner flying; along with Richie Spice, Tarrus Riley and Jah Cure.

GLOBAL APPEAL

Reggae and dancehall are officially world-renowned music, from Mavado’s ‘Real McKoy’ being used as part of the trailer for the video game Grand Theft Auto 4, to Sean Paul’s 2012 album ‘Tomahawk Technique’ seeing world chart action. Shaggy’s 2000 album ‘Hot Shot’ has sold over 20 million copies worldwide; Damian ‘Jr Gong’ Marley is part of the SuperHeavy group with Mick Jagger and Dave Stewart; and Horace Andy continues to do lead duties for British band Massive Attack. There are reggae festivals held all over the world, with the European summer circuit that includes Reggae Geel (Belgium) and Rototom Sunsplash (Spain) especially famous. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery then Jamaica should be truly flattered that the sound system – the bedrock of Jamaican popular music – has been replicated all over the world. One, the Japanese outfit Mighty Crown, conquered all comers to win the 2007 Death before Dishonour clash in Montego Bay, St James.

Now, as Jamaica celebrates its 50th anniversary, singjay Vegas has made a striking, deliberate effort to combine the two forms with his album ‘Sweet Jamaica’, a double CD release with one disc roots reggae and the other dancehall. It is representative of the coming together of the final stretch of the Jamaica Music Museum’s 22 yards – and centuries of Jamaican popular music history.